Conceptualising fertility decision-making and behaviours (cont.)

Norm, Desire, Expect, Intention and Plan

The terms fertility preferences, desires, intention and plan are often used interchangeably in demography. Although it is uncertain whether individuals and couples distinguish between these subtleties of meaning, these terms carry different meanings.

Many surveys ask for an ideal number of children. Answers to this question reflect social norms or values as well as personal values. People may provide desirable, acceptable, or typical number of children to this question rather than their own desire.

Fertility desire may be derived from answers to the questions on what respondents "want" or "desire" (Casterline and El-Zeini 2007). Desire is the most idealised personal preferences, without assuming any constraints, and may be based on emotion. For instance, an infecund woman or man may "desire" to have a child.

Expect takes into account constraints, unlike desire. Fertility expectation is a preference which considers the factors that may facilitate or impede putting their desire into action, and the perceived power of these factors. For example, a 35-year-old woman with 5 children who wants no more children may expect to have another one due to lack of access to family planning.

Intention implies commitment to a set of behaviours to have or not to have a child (Kodzi et al. 2010). The term ‘intention’ conceptually bears a more specific and realistic concept of preferences pertaining to individuals and taking into account diverse constraints, such as time, health and costs. It has elements of planning (Stanford et al. 2000). For instance, a woman who has a 1-year-old child may not intend to have another child within a year because of financial constraints.

Plan is an extension of intention and embraces anticipatory behaviour (Barrett and Wellings 2002). For instance, a woman who is planning to have a baby soon may stop alcohol drinking and start recording her monthly menstrual cycles to identify timing of ovulation, in addition to stop practicing contraception.

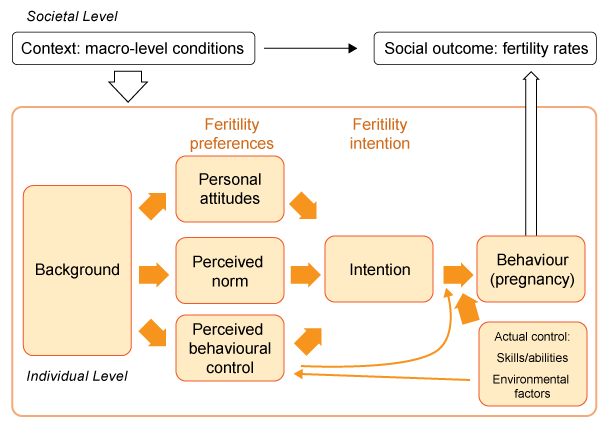

In recent years, some demographers draw on socio-psychological theories, such as the theory of planned behaviours (Ajzen 1985), to understand decision-making processes of childbearing. In this theory, intention is formulated by: a) personal attitudes towards the behaviours (e.g. childbearing); b) subjective normative belief; and c) perceived behavioural control, i.e. perceived ability to perform their behaviours. Actualisation of intention is subject to actual control of fertility and perceived behavioural control.

Figure 1: Theory of planned behaviours

Source: adapted from Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), Testa, Sobotka and Morgan (2011)

The theory of planned behaviours is useful in understanding how social norms, individual desire and perceived behavioural control are translated into reproductive behaviours. However, it is uncertain whether individuals and couples can distinguish between these concepts. Moreover, pregnancy is not always the outcome of reasoned action, and unintended pregnancy may be driven by motivations which do not reflect conscious decisions to pursue a given target. The limitations of this intention-based approach are extensively discussed in 8. Validity and predictive value of reproductive preferences ![]() .

.

Regardless of the shortcomings, many studies have shown that fertility preferences and intentions have an independent effect of predicting future childbearing. The preference is an essential input for estimating unmet need for family planning and demand for contraceptive commodities, and understanding aggregated fertility patterns and childbearing norms in societies.

Self-reported preferences to the explicit questions discussed above help us understand reproductive decision-making as well as actual behaviours. But the preferences can be also revealed by examination of reproductive behaviours, such as parity progression ratios or contraceptive use classified by number of children. The next page discusses this approach.