Variation around the world and differences between men and women

A global review of sexual behaviour (Wellings K et al. (2006). Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet 368(9548): 1706-1728 - http://www.sciencedirect.com/science ![]() ) revealed diversity between countries but also some broad similarities. Monogamous marriage is the dominant pattern of sexual partnership, and most sex occurs within such partnerships. Multiple partners are reported more often by men than women, and more commonly in industrialised countries than in those badly affected by HIV.

) revealed diversity between countries but also some broad similarities. Monogamous marriage is the dominant pattern of sexual partnership, and most sex occurs within such partnerships. Multiple partners are reported more often by men than women, and more commonly in industrialised countries than in those badly affected by HIV.

![]() Click on the tabs below to see global variation as well as differences between men and women.

Click on the tabs below to see global variation as well as differences between men and women.

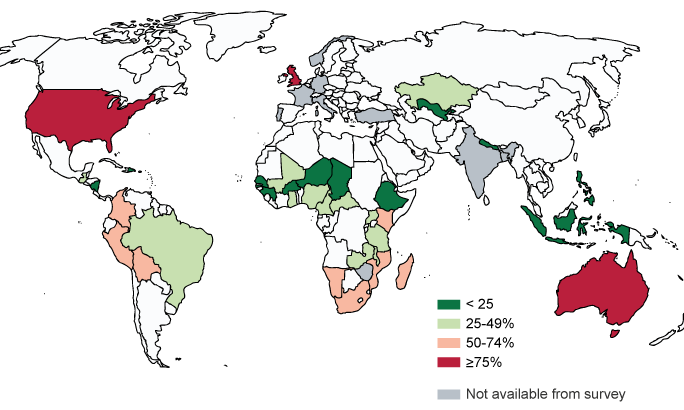

Maps adapted from Wellings K et al. (2006). Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet 368(9548): 1706-1728

Young people’s sexual activity is often sporadic. Age at first sex has fallen in many populations in the last 20-30 years, but increases in the age at marriage are at least as important in creating a longer period of pre-marital sexual activity in many populations.

Data remain scarce for some population groups and some geographical regions, reflecting local attitudes to sexual behaviour and priorities for health.

Below is a summary of the key messages from Lancet global review:

Information about sexual behaviour is essential to inform preventive strategies and to correct myths in public perceptions of sexual behaviour. Increased research in this area in the past two decades provides a historically unique opportunity to take stock of sexual behaviour, and efforts to safeguard it, at the beginning of the 21st century. Gaps in knowledge remain, especially in Asia and the middle east, where obstacles to sexual-behaviour research remain.

Trends towards earlier sexual experience are less pronounced and less widespread than sometimes supposed (in many developing countries the trend is towards later onset of sexual activity for women), but the trend towards later marriage has led to an increase in the prevalence of premarital sex.

Most people are married and married people have the most sex. Sexual activity in young single people tends to be sporadic, but is greater in industrialised countries than in developing countries.

Monogamy is the dominant pattern in most regions; but reporting of multiple partnerships is more common in men than in women, and generally more common in developed countries than in developing countries.

Striking differences between men and women in sexual activity are explained in part by a tendency for men to over-report and women to under-report, but patterns of age mixing and the age structures of populations also help explain the difference, especially in African countries.

Marriage does not reliably safeguard sexual-health status. Married women find negotiation of safer sex and use of condoms for family planning more difficult than do single women. Very early sexual experience within marriage can be coercive and traumatic Condom use is increasing—in some cases, such as in Uganda, strikingly so—but in many developing countries, rates of use remain low.

Factors that determine variations and trends in sexual behaviour are environmental and include shifts in poverty, education, and employment; demographic trends such as the changing age structure of populations and the trend towards later marriage; increased migration between and within countries; globalisation of mass media; advances in contraception and access to family-planning services; and public-health HIV and sexually transmitted disease prevention strategies.

Public-health interventions should address the broader determinants of sexual behaviour, such as gender, poverty, and mobility, in addition to individual behaviour change.

Risk-reduction messages should respect diversity and preserve choice. Selective emphasis on different aspects of the ABC strategy needs to be tailored to individuals and settings. Young people need to be helped to achieve the best timing of first sex, but first sexual experiences are often forced, or even sold.

School-based sex education improves awareness of risk and knowledge of risk reduction strategies, increases self-effectiveness and intention to practice safer sex, and delays rather than hastens the onset of sexual activity.

No general approach to sexual-health promotion will work everywhere, and no single-component intervention will work anywhere. We need to know not only whether interventions work, but why and how they do so in particular social contexts. Comprehensive behavioural interventions are needed that take account of the social context, attempt to modify social norms to support uptake and maintenance of behaviour change, and tackle the structural factors that contribute to risky sexual behaviour.